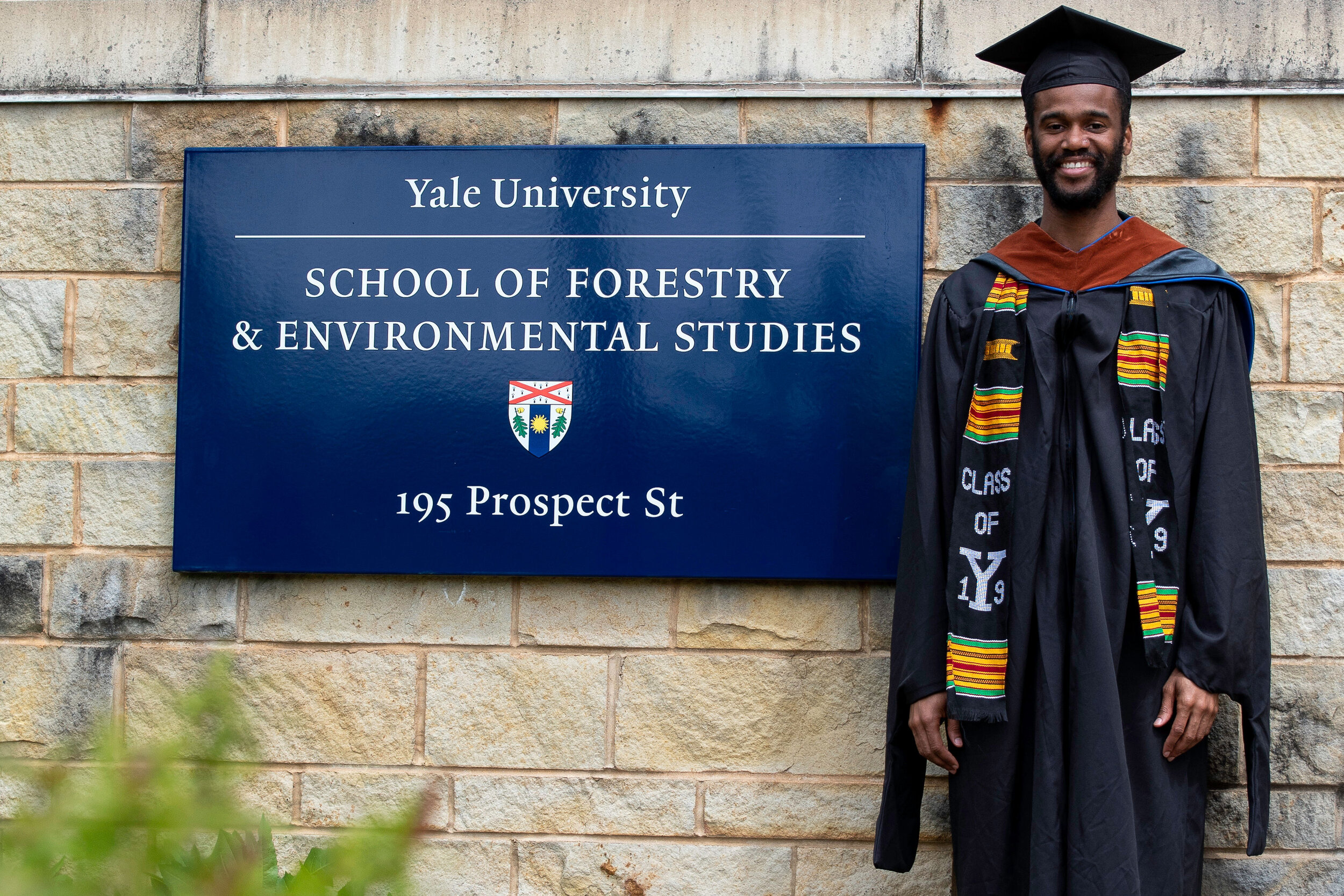

A Black Man who happened to graduate from Yale

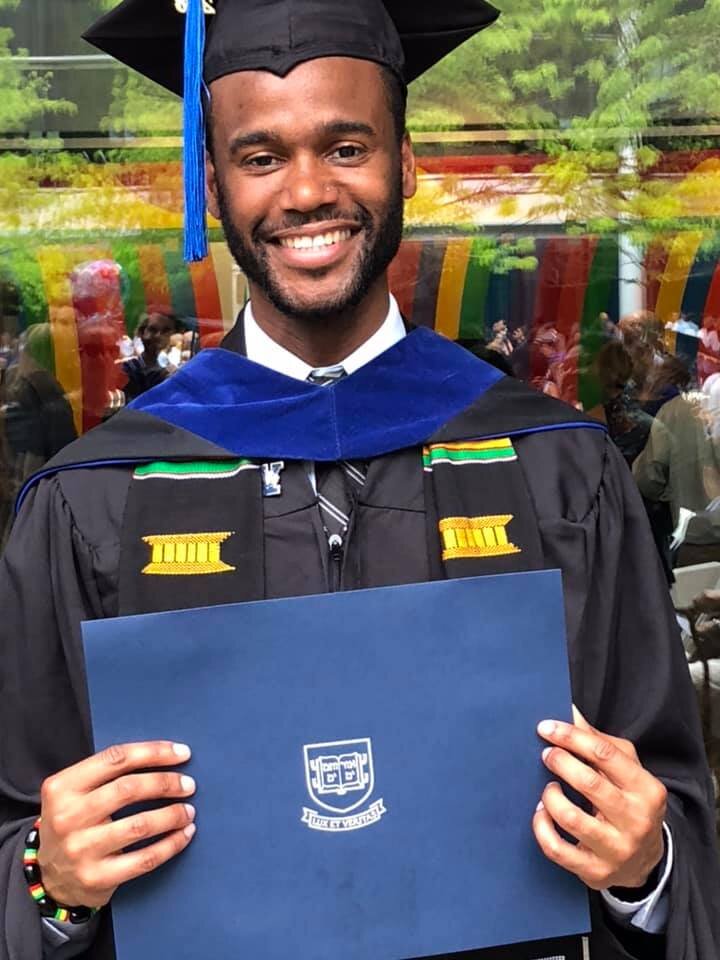

Last month, I graduated from Yale University with two master’s degrees. This is huge for my family. I’m incredibly proud and grateful for all who’ve poured into me. Yet, I’ve been grappling with the complexities. How can I celebrate during a pandemic that’s disproportionately impacting my community? How can I take joy when Black people continue to be dehumanized, excluded, and assassinated? This is my attempt to hold space for the both/and.

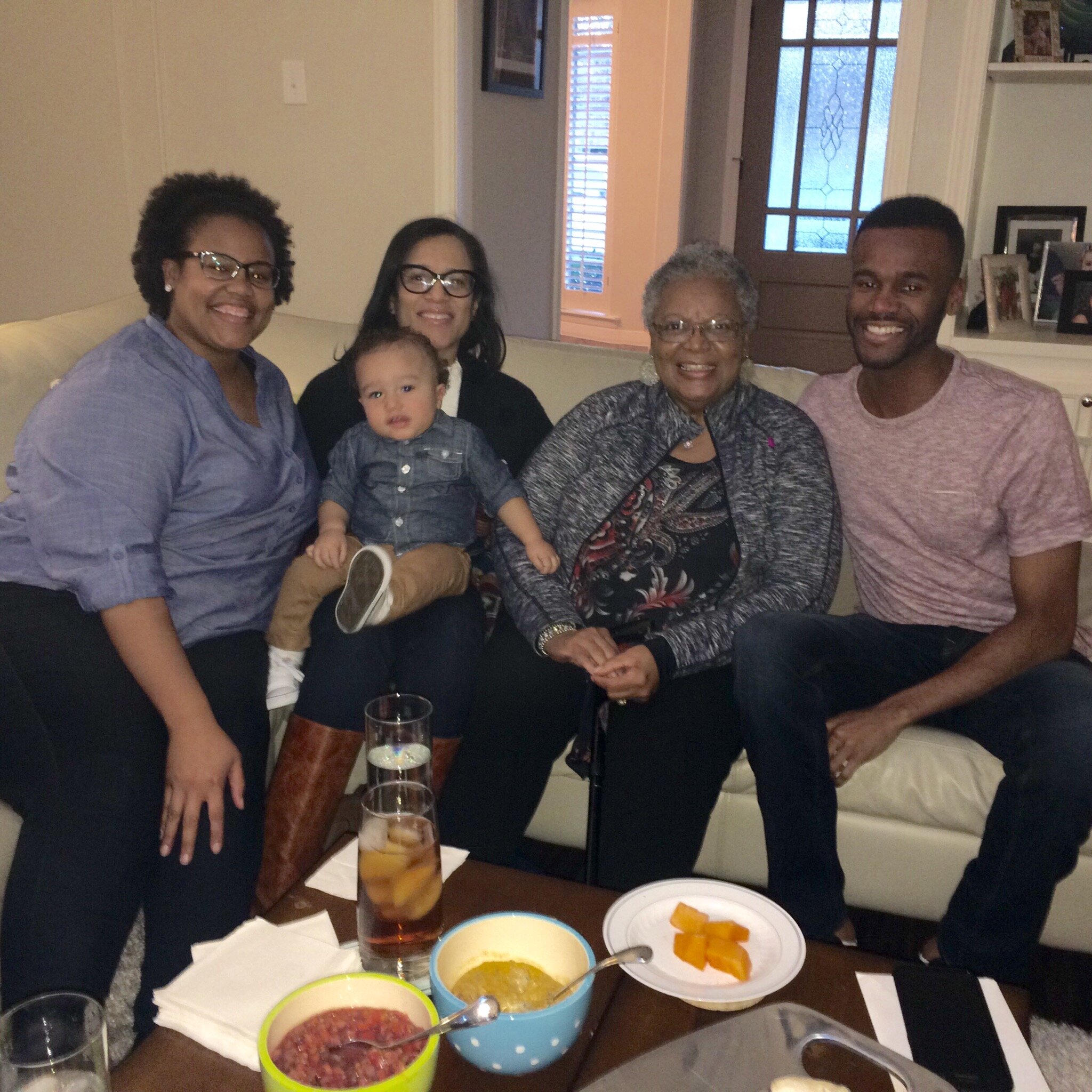

“Ohhhh weeeeeeeeee! So proud, how I wish my parents and grandparents were here to see this day. I love you always.”

I can almost hear my Gram saying – no, squealing – those words to me. I can feel the accompanying tight embrace. And I can taste the celebratory banana bread that she would have whipped up for me. But this time, her words come in an email. Coronavirus has made everything virtual. That includes my graduation from Yale with an MBA and Master of Environmental Management.

Gram, my mom’s mom, is my only living grandparent. Even through cyberspace, she warms and comforts me. And, she fulfills her duty as the tribe’s elder, the matriarch: She prompts me to reflect on this moment within the context of my family’s history.

Family. History.[1]

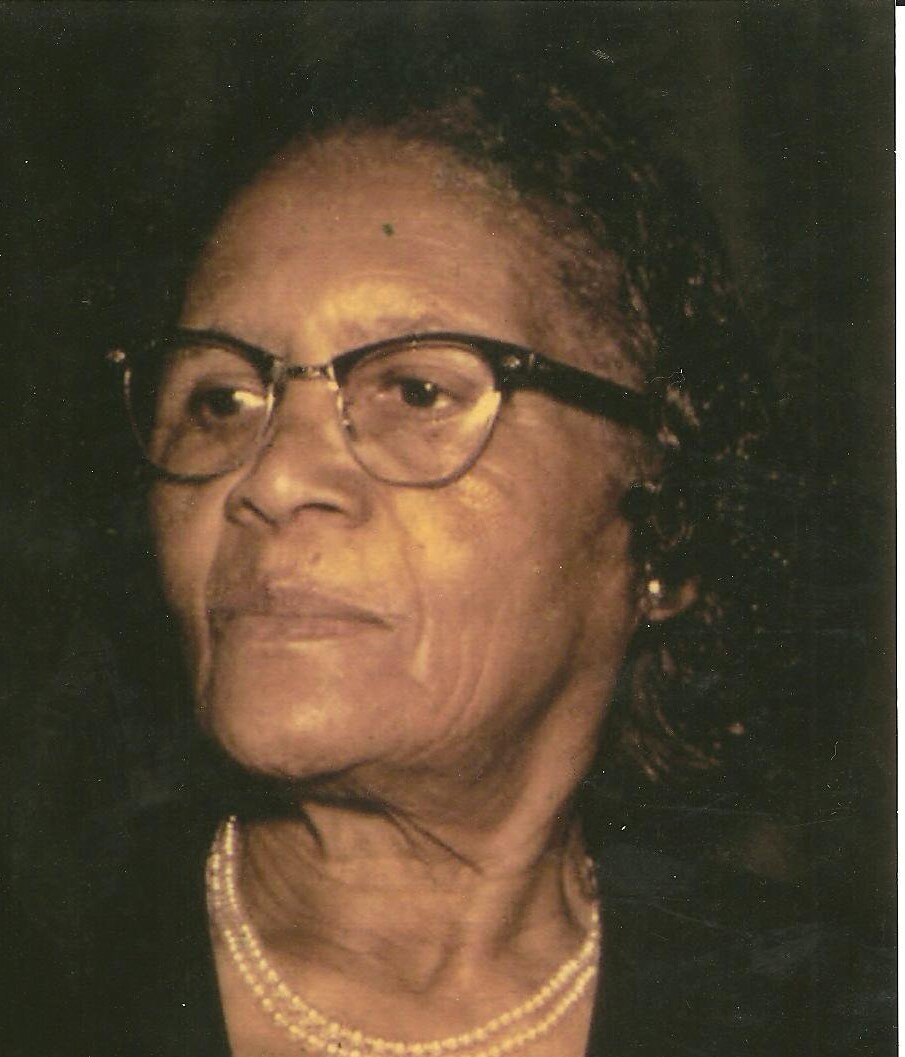

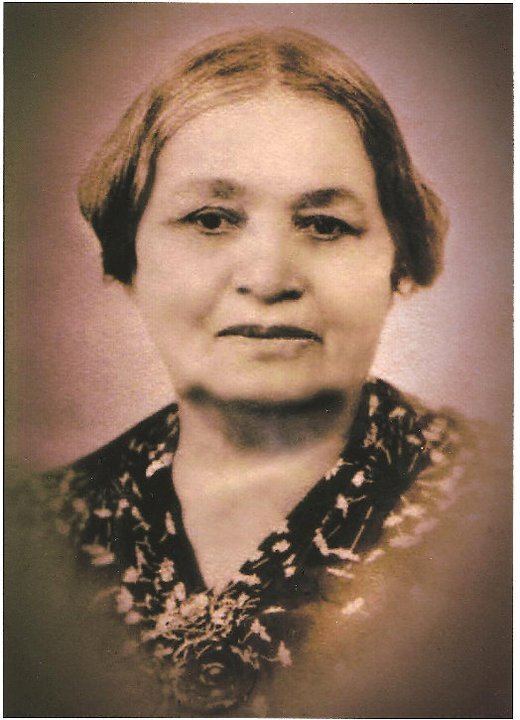

Gram grew up in a rural town in Nova Scotia, Canada. After the British lost the Revolutionary War, several Black Loyalists – including former slaves – moved to the province. Gram’s father Ericks Langford fought in WWII. He was a lumberjack and an avid reader of the Bible. He was also an esteemed raconteur, luring flocks of people to their house to hear him tell stories. Gram’s mother Annie was a force. The house that people flocked to – she built much of it with her bare hands while the men were away at war! She was a gifted caretaker, extending her nurturing attention to gardens, farm animals, and people in need. Although Gram didn’t have extensive formal schooling, she loves to learn and epitomizes excellence. Into her eighties, she continues to teach me - by example - about leadership, civic engagement, hospitality, and community service. I’m in awe of her.

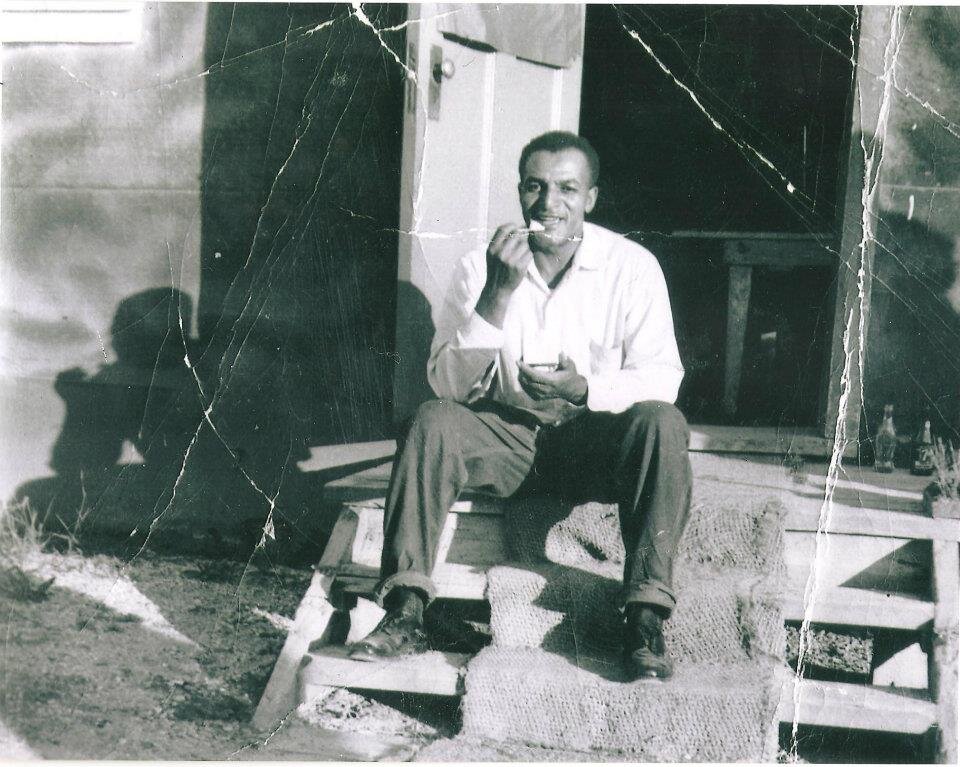

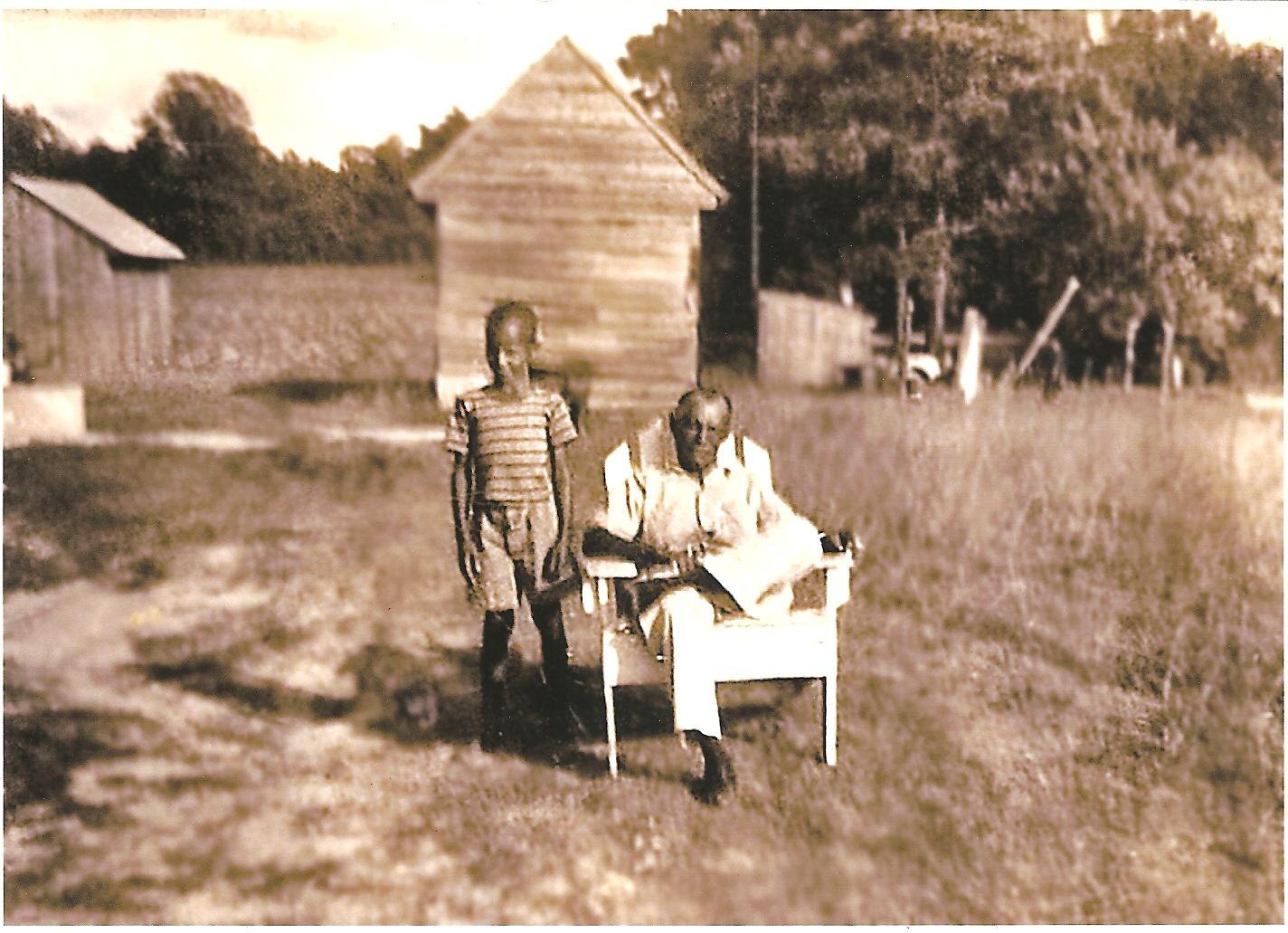

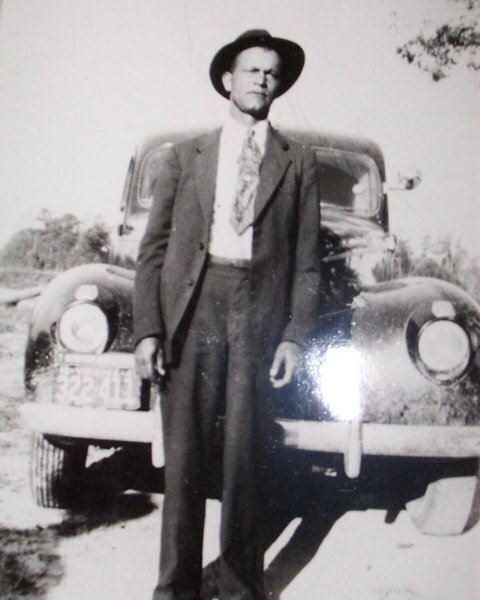

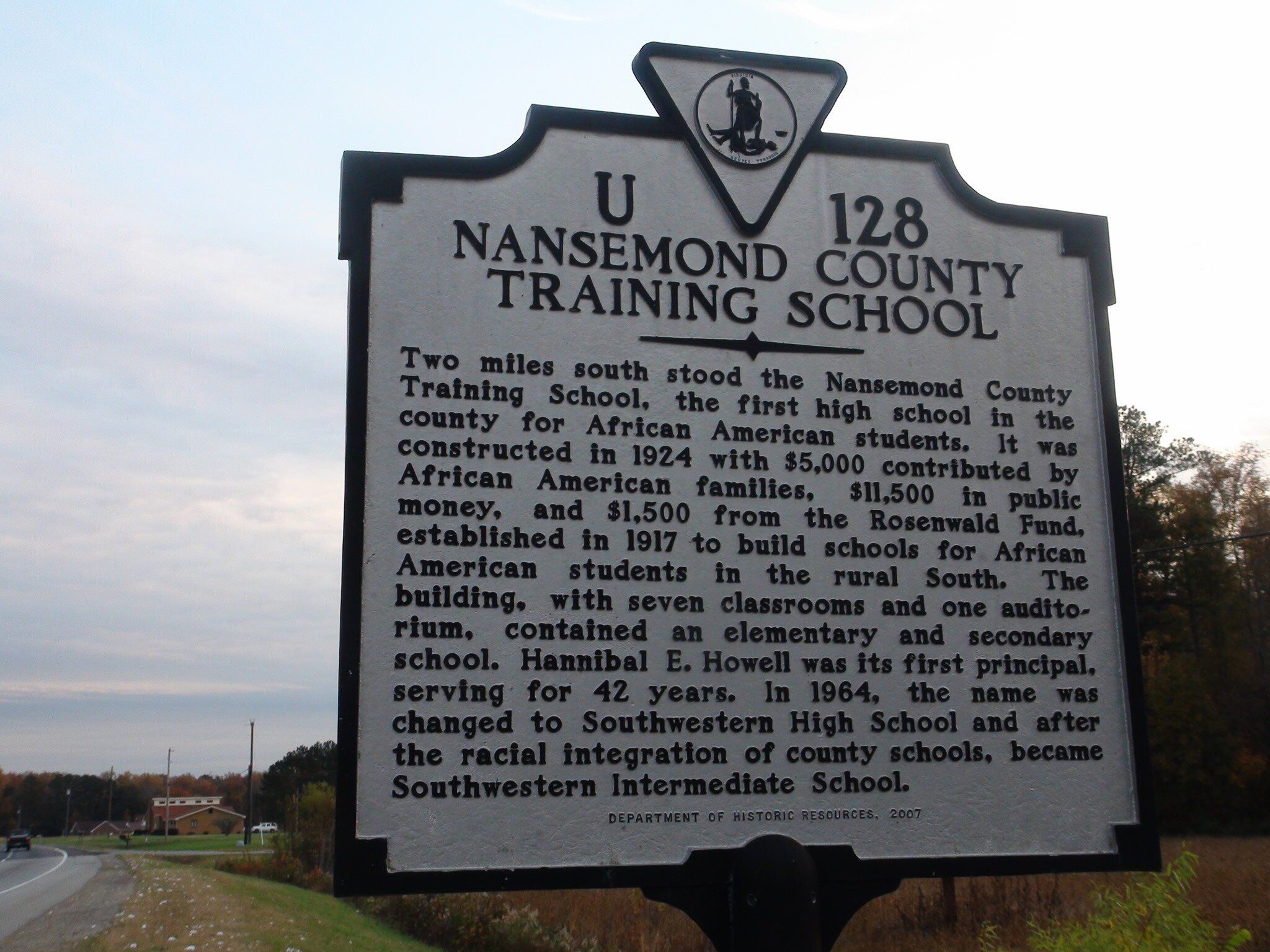

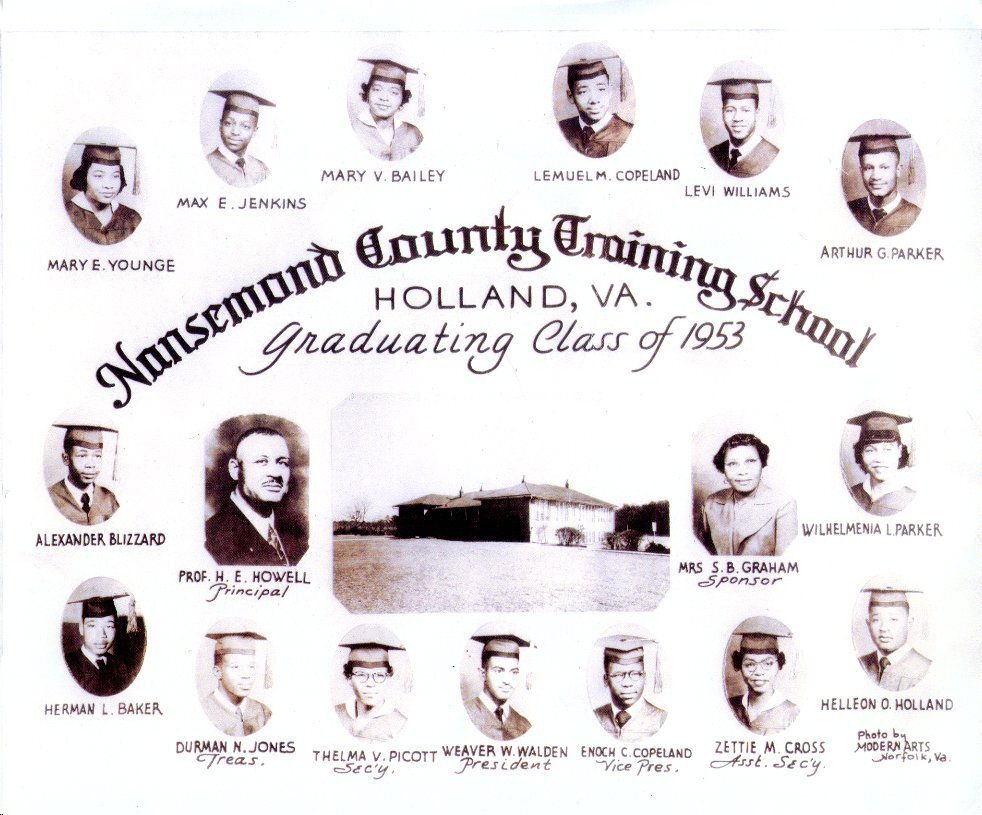

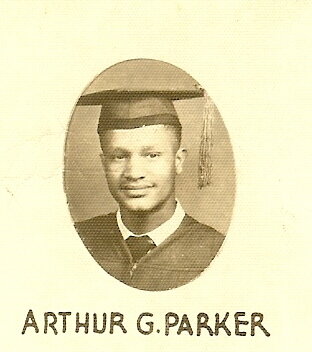

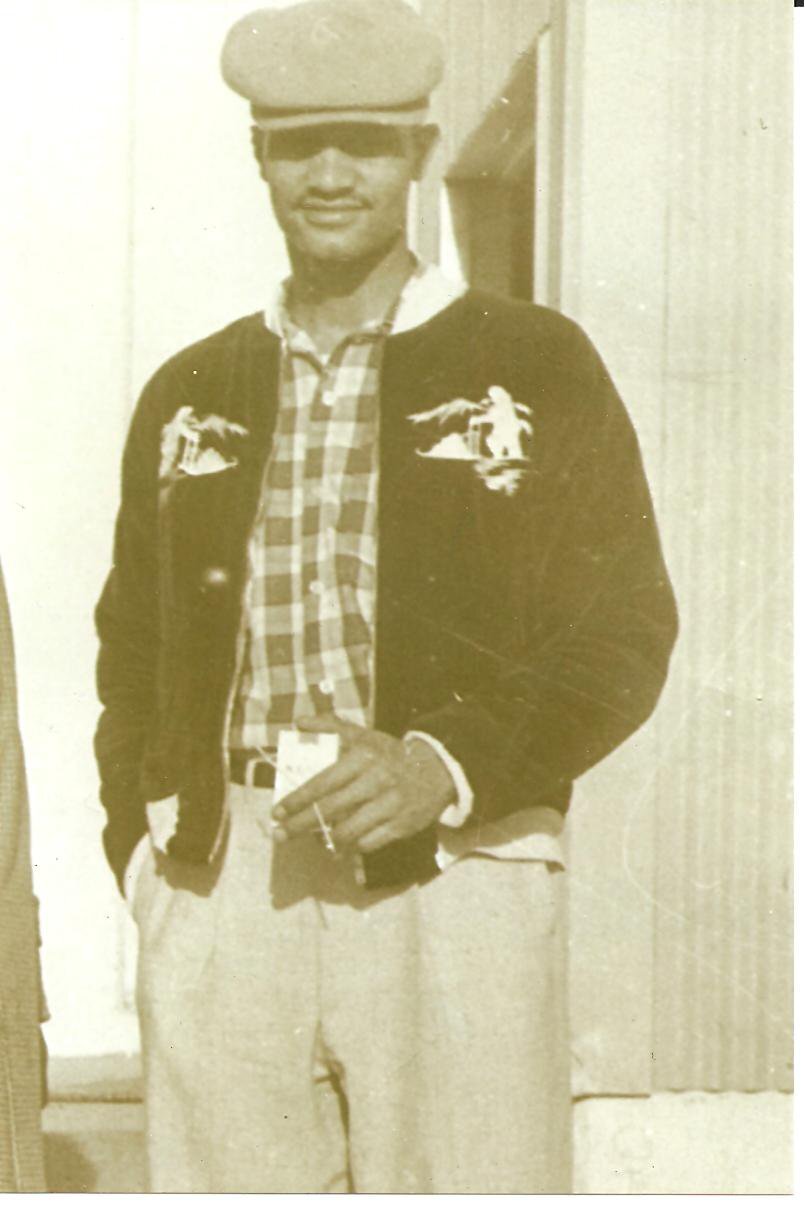

Granddad, Gram’s late husband, came from a sharecropping family in southern Virginia. His mother, Lucy Emma was the granddaughter of a former slave, Roxanna, and Roxanna’s former “owner.” As a sharecropper, Granddad’s father Henry Parker experienced the economic exploitation that continued for generations after slavery ended. Granddad attended Nansemond County Training School, the local school for Black students. Unsurprisingly, it lacked many of the resources that White schools had, including books, electricity, and bus transport services. Still, Granddad graduated in 1953 – a year before Brown v. Board. He then built a career in the US Air Force, as the military was one of the few options for Black men.

We’ve come a long way from bondage and tree chopping and training schools. I’m proud. I honor the strength, resilience, love, and sacrifice of my Ancestors, whose blood dances in my veins. I carry them with me. My children will know a different reality.

But it’s complicated.

It’s not lost on me that most of the Black Americans – descendants of slaves – on Yale’s campus are cleaning buildings and serving food. As we’ve seen in this pandemic, that work is honorable. Essential, in fact. But it’s mostly thankless. And it leads to far fewer opportunities than I now have.

It’s not lost on the campus workers, either. My first week on campus, one of the building custodians, Mike, approached me. He was around my age, maybe a little younger. “I’m proud of you,” he offered. “You’re doing this for us. We’re pulling for you.” We both understood what that meant. Very few Black folks have access to this world that I now inhabit. For example, by my estimation, there are 13 Black Americans in the graduating classes of both of my graduate programs combined. Thirteen. Out of approximately 500. That’s 2.6%.

The legacy of slavery and legal apartheid runs deep. There are countless structural and institutional injustices beyond underrepresentation at elite graduate programs. I’ll spare you from that list. Then, on the individual level, there’s the daily trauma of being surveilled, fearing encounters with police, having to prove that we’re nice, smart, normal people, too. Frequent personal experiences, news stories, and hashtags reiterate that our efforts don’t matter. Neither do our lives. This reality has material and psychological consequences that make mere survival a feat worthy of praise. For too many Black folks, attending Yale is an impossibility long before it can even become a dream.

I’m an exception to the rule. A statistical outlier. In several ways, I’ve gotten lucky. So, my graduation from Yale is not only symbolic for my forebears. It’s symbolic for my contemporaries, for my community that’s been left out, never given a real chance. What does Mike’s Gram say to him? What about his ancestors?

Actually, I don’t think the dream of our ancestors was for their offspring to graduate from prestigious, exclusive universities. I don’t think their dream was that we sell our labor at the highest price to the most reputable companies. Those are markers of success within the confines of a stratified, competitive capitalist system. That’s the world we live in, but we’re so much more than that.

Their dream was transcendent.

I believe that our Ancestors dreamed of liberation and joy – for every body. For every mind and soul. They dreamed that, anchored in love, we’d have the freedom, the resources, the opportunity to self-actualize. To become who we were created to be. To commune with each other and with the Earth. To remove luck from the equation.

I believe that they’re still dreaming that unrealized dream.

So, yes, this moment is significant, a BFD. I relish it, and the progress that it represents. I acknowledge the undue power and platform that come with it. I extend gratitude to the Teachers, Guides, and Loved Ones who’ve led me here. At the same time, we have work to do. I have work to do. These gifts, these privileges are not mine to keep. I must move towards my self-actualization, and create space for others to reach theirs. That work can and must take many forms.

I sense the gravity of this moment. I’m aware of my responsibilities to my ancestors and to my community. I’m scared. I feel uncertain about which path is the most noble, which step is right. I’ll keep searching, listening for the inner Wisdom. And with Hope, I’ll pursue our collective inheritance.

[1] I’m thankful to Gram and Uncle Bill and Cousin Teresa for so generously sharing these stories with me. Gram has shared them through conversation, and she’s gone to great lengths to write some of them down. Uncle Bill and Teresa are the first cousin and niece of Granddad. They recounted family stories and shared family documents/photos that were immensely helpful. Thanks also to Uncle Junior who had some great family photos posted on social media.